- Home

- Rachel Halliburton

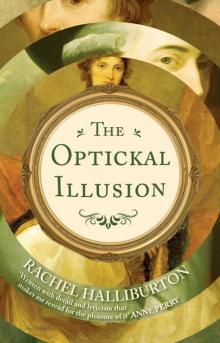

The Optickal Illusion Page 2

The Optickal Illusion Read online

Page 2

‘When have I made others suffer?’

‘What of your fiancée, Elizabeth, right now? You were to be married this summer. What is she going to say?’

Benjamin took a deep breath.

‘I would not be who I am if I did not take this opportunity. I hope and pray that she will be content to await my return.’

He groped to say something more. Of the struggle he felt it had been to become a painter. Of how he was no natural scholar, so every fact and technique he had mastered was a triumph of stubbornness. Of how the words jumbled in his head when he read books, so he had learnt to make a virtue out of learning through experiment and conversation, doggedly taking apart each idea he was told and building it up again until it finally made sense. Of his instinct that this journey would teach him a hundred times more than black marks on a page. Yet he saw the expression on his brother’s face, and realised that rather than explain this, it was wiser to say nothing.

‘So she believes you will return?’ William said finally. It was as much a question as a challenge.

‘I am going to Europe.’ He attempted weakly to make a joke: ‘I will not fall off the edge of the world. I will be back by the end of the year.’

William shook his head.

‘You may tell yourself that is true. But I will certainly not waste my time by believing it.’

He stalked out of the room and into the night.

Italy

When the ship eventually docks in Pisa, the land appears to rock beneath Benjamin West for two days. His sense of elated terror is added to by the fact that in 1760 he is the only American that most Italians have met. He realises quickly that many who encounter him judge him as a curiosity. He squirms under their scrutiny like a clam prised open by a bear.

Before arriving in Italy, he has imagined it as a world of fantasy. A mountain range of domed cathedrals; ancient libraries filled with papery whispers; metallic choruses of bells and alleyways dirty with history. His head has been filled with myths of babies suckled by wolves; with glittering treasures stored by the Medicis; with a land lofty with pagan gods and bombastic with popery.

But reality comes with a twist. Within a few days he begins to realise that he is engaged in a fight he had not anticipated. He has English grandparents, so considers himself to have an affinity with Europe. Yet the Italians he meets view it differently. Quickly he sees that many of them are not just ignorant of his own culture, they are contemptuous of it. He discovers this with most embarrassment on the afternoon that a cardinal takes him on a tour of the Vatican with a group. The cardinal’s holiness has a stench of condescension – he quips loudly on meeting West that he is disappointed to realise he is not a Native American.

West starts to talk about the summers he has spent hunting and shooting with tribesmen, about the painting techniques he has learnt on the riverbank. But with a swift turn of the head, the cardinal indicates he is not interested in a reply of any kind. West feels cowed until, towards the end, they come to the seven-foot-high statue of the Apollo Belvedere. Turning to the group, the cardinal describes it in pinched, saintly tones as the greatest classical statue in existence, the embodiment of physical perfection, one of Italy’s greatest treasures. His words drift in the arid air. West stops listening to him – stares at the statue to see what his instincts tell him. And suddenly he feels as if he is back in Pennsylvania again. He sees that it has been sculpted to look as if it has just fired an arrow, sees the tension of the muscles, the tilt backwards of the body, the strange sense of blood flowing vigorously beneath the stony flesh. Filled with pride, he declares, ‘Now this is worthy of comparison with a Mohawk Warrior.’

But he has miscalculated. The laughter and gasps rise around him. He looks at the cassocks, breeches and waistcoats, the cerebral expressions, the bodies corseted by decorum. He sees how he has been judged vulgar for associating the naked statue with a living breathing man. He feels angry embarrassment that what he has intended to be a compliment has been seen by everyone else as an unacceptable mockery of a classical ideal.

As the outrage increases, West realises that just as he must learn to understand the Europeans’ continent, he must battle to make them understand his. Here in the Vatican art suddenly seems to be about ghosts fermented in wine and trapped in stone, the voices of a thousand dead men, dust and superiority. He vows to master every technique he can, while never forgetting the mountains, forests and endless skies of the landscape that has made him. In Florence he perfects chiaroscuro and gazes endlessly at green-faced Madonnas, in Ravenna he stares at mosaics that shimmer like fish caught by the morning sunlight. In the cutthroat salons of Europe’s intellectuals he gradually starts to gain acceptance.

His letters home show none of the problems he encounters. They mark the triumphant progress of a young American abroad. He never mentions the frequent bouts of illness that hint at his unhappy state of mind, even when he is laid low for months in Florence. He does not talk of the times that he wishes he were just a canvas on a wall, the times that a snide remark makes him wish to punch someone, the times that he aches to smell Pennsylvanian air again. At this point it is only the pressure of paying his patron in new artworks that stops him from returning home before the end of the first summer.

And then the tide turns. He cannot say exactly how and when that is. There is no steady progression – just advances and retreats, shimmers and surges. Small epiphanies, such as the evening where he arrives in Venice. A sense of fantasy about what he observes, as if it is all a figment of a sea-god’s imagination. Something dirty about the beauty – the history of each palazzo imbued with bloodshed, licentiousness, poisoned rivalries and corruption. He sees Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin Mary – a painting that once reinvented composition and colour, and it turns him inside out. The clashes of reds and golds, Mary smaller than the apostles and yet more vivid, a sense of swaying and light. In Florence, Massaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden will also give him a sense of broken rules and liberation. Bodies hunched with despair that somehow speak of a new world. A sense of eloquence that he cannot precisely describe. Yet he tries to reproduce it again and again in shabby notebooks.

Brushstroke by brushstroke, Europe starts to change him. He discovers like minds, wins accolades, starts to walk taller and prouder. The months abroad turn to years. Each time he puts a date on a letter that he writes home, he realises his brother is winning their argument, but he is starting to enjoy the new rhythm of his life, the continuing sense of fresh perceptions, the belief that he is gaining hard-won respect. As the commissions flood in, any sense of guilt is drowned out by the louder noise of opportunity. In the salons he is known as ‘The American’ – where once the description was a form of disdain, now it is a warm acknowledgement. He thinks he has won a victory. Yet he does not recognise how the word ‘American’ is like a hinge from which attitudes will swing back and forth throughout his life. Right now it is a term of acceptance, but in the more distant future it will adapt equally easily to tones of hostility, fear, and even mockery once again as the world around him changes.

It is on an early evening in October 1762, when the stones of Rome seem saturated in gold, that he decides he should delay his return to the country he professes to love no longer. He sits and writes letters to both his family and fiancée that he will be back in the spring. But for reasons he cannot entirely understand the pieces of paper are still sitting on his desk a week later when a letter arrives from his patron. He breaks the seal while eating bread and partridge at breakfast. In it is an invitation to London. It is the work of a moment for him to accept it.

Britain

A set of two pictures. In the first, it is 1763. The sky is grey and hurls down raindrops like mockery. West is not sure yet what attracts people to this city. The Thames and its ferment of corpses and excrement seems no substitute for either pure blue Pennsylvanian lakes or the warm Mediterranean. He has little conception that he will spend the rest of his life here. What he

does know is that though he has travelled more extensively than many who are twice his age, he still feels less educated and articulate than the wits and fops who see themselves as the city’s predators.

All these details lie outside the frame. Inside it is the self-portrait West creates that year. Some might call the image a lie, others a paradox. Still others might call it a declaration of intent. There is no sign in this picture of how disconcerted he feels. He sports a grey powdered wig with panache, while his black hat is tilted at a jaunty angle. He has the full-blooded complexion of one who is in good health, while his long straight nose lends him an air of distinction. One half of his face is in shadow, so that just one dark eye stares at us as if to challenge us. With his left hand he clasps an easel. In this moment, the portrait of the artist is more substantial than the man it represents.

Soon, however, the image and reality will conflate. The arc of ambition that William has noted is carrying West upwards, and wealthy patrons and acclaim are waiting in the wings. In London, the teeming city – with its vagabonds and tradesmen, exiles and patriots, dukes and beggars, opportunists and innocents waiting to be corrupted – he will be one of the survivors. Within a month he will write to his mother that he has an introduction to the King.

And then there will be one political revolution. And after that a second. All certainties will rise up into the air like ashes from a fire. The young man’s portrait is replaced by that of a fifty-eight-year-old. A man both augmented and weighed down by his experiences, the pink bloom in the cheeks replaced by vascular red threads, the eyes corrupted by uncertainty. A man whose upright shoulders show he is well acquainted with the taste of success yet whose bitter set of the chin demonstrates he is not a little marked by the scourges of envy. A man who has learnt that all that was once unpredictable is now even more unpredictable, for whom the edict that the only true wisdom is in knowing one knows nothing rings darkly true.

A man for whom, right now, the Provises are just shadows in a world of shadows. All he knows is that they exist, and that finally the laws of chance have seen fit to cross their path with his. They are somewhere out there amid the passing carriages and the clatter of horse-hooves, their voices just more sounds amid the beggars’ cries, paupers’ wails, whorehouse groans, and tattle of aristocrats. London is the teeming city, filled with all manner of humankind. What do they really have to offer in this, the world’s largest city, so many bodies pressing themselves together in the dirty streets seeking the hope that somehow they cannot find in the green fields beyond?

CHAPTER TWO

St James’s Palace, residence of King George III, London, 1795

‘Gall Stone is found in the gall of oxen. It is of different forms, sometimes round, at others oval. Ground very fine upon Porphyry; it produces a beautiful golden Yellow. It can be used for Oil Painting, though rarely: it is chiefly used for Miniature and Drawings in Watercolours.’

constant de massoul,

A Treatise on the Art of Painting and the Composition of Colours, 1797

Mrs Tullett, seamstress to the Queen, has arrived at the living quarters of Mr Provis – verger to the Chapel Royal – to help prepare his daughter for their visit to Mr West. Yet the matter in hand is never her favoured topic of conversation, and for an hour now she has been railing about the catastrophic state of the world around them.

‘Until the last moment the King had not the slightest idea of the danger she posed.’ Her eyes grow large. A drab woman with a rasping voice, she is a scavenger for misfortune. As she talks, fat fingers shuttle back and forth in the air, between those fingers a silver needle glints. In the other hand a delicate headdress starts to take shape.

‘He was getting out of his carriage to greet the crowds,’ she continues, ‘as he had hundreds of times before…’

The needle pauses. The Provises exchange glances.

‘A woman came up to him who had the appearance of a domestic servant. She was holding a sheet of paper out to him, which he thought was a petition of some kind. So of course he took it. But underneath it was a knife…’

The girl, Ann Jemima, stares questioningly at the man who nods affirmation. Mrs Tullett’s voice becomes cold, admonitory.

‘She could have killed him there and then. But she didn’t. The blade was too cheap, it left no mark, and King George walked away saying he felt sorry for her…’

Mr Provis reaches over to the tray on the table between them, and takes the lid off the engraved silver pot sitting on it. The smell of coffee punches into the air. He looks at Ann Jemima sitting demurely. Senses her scepticism as the story becomes ever more sensational, sees her eyes flash with amusement at Mrs Tullett’s more ghoulish flourishes. Later they will mock the old crone’s predilection for disaster. ‘She was hatched from the egg of a carrion crow,’ Ann Jemima has often declared. But for now they flatter her with compliments that will turn to dust once the door has closed behind her.

It is Ann Jemima who has decided that Mrs Tullett should be invited over from the Queen’s residence at Buckingham House to help her dress for the visit to Mr West. Though Mrs Tullett is now a needlewoman in the Queen’s Wardrobe, she has worked her way up from scullery maid, and has known the comings and goings of the palace for almost thirty-five years. She is bulky with regrets. The weather system of her moods goes from stormy to overcast, the sun rarely glimpsed.

She talks often about how she started at the court in the same week that the then young and naïve Queen Charlotte arrived from north Germany. She has a memory of creeping into the back of the Drawing Room where celebrations were being held following the wedding service. Of seeing the lights blaze like constellations, hearing the symphony of clinking glasses, velvet chatter and song. Amid the finery it was a shock to realise that the royal bride was as dark and ugly as she herself – and yet could be the source of so much admiration.

Today the three of them are sitting in Provis’s own much more humble drawing room. As Groom of the Vestry at the Chapel Royal, he lives in a small apartment on Green Cloth Court at St James’s Palace. Of the seven courtyards around which St James’s is built, Green Cloth Court is one of the largest. Yet Provis’s own residence is modest in scale – ‘Put a microscope on it,’ he tends to joke, ‘and you may see a residence fit for a flea.’

The microscope would also reveal his living quarters as a retreat filled with curiosities. It startles all who enter it for the first time. The ivory sphinx that guards the mantelpiece, the framed copies of Hogarth’s Mariage A-la-mode that hang above it. The Venetian skeleton key that dangles from a cord by the window. The Indian white jade cup with a goat-shaped handle. All bear testimony to a passion for the esoteric and exotic that would seem more fitting for a man with five times his income. Yet he has not come by any of his possessions through dishonest means, but – as he often reminds people – through a talent for seeing treasure where others see only dung. More than one market-stall holder has yielded an object up to him for a ha’penny that would be fit for any stately home after a bit of polish and loving care.

He places the lid back on the silver coffee pot and pours them each a cup. ‘The woman’s name was Margaret Nicholson. She was trying to attack him with a dessert knife I believe…’ he says dourly. ‘She was aiming for his heart, but only managed a swipe at his waistcoat. She’d have had as much luck trying to assassinate him with a teaspoon…’

Ann Jemima can suppress her laughter no more. Mrs Tullett darts her a resentful glance. The girl swiftly recovers herself.

‘Mrs Tullett is right – it could have been most grave.’ She takes a deep breath, and is demure again. ‘How could a madwoman approach the King so closely? She could have done the deed if she’d had the right weapon.’

‘That’s what everyone was saying at the court.’ Mrs Tullett noisily sucks the end of a piece of cotton before threading it through the needle again. ‘But the King refused to take it as a warning. He continues to go out into the crowds at every opportunity, saying he does

not fear malefactors.’

‘And by and large he has been proved right,’ says Provis briskly.

‘Until five weeks ago,’ declares Mrs Tullett.

They are all quiet for a moment. Provis’s fingers drum a dirge on the table, while Mrs Tullett leans over to reach the sugar tongs.

‘In this more recent attempt the King was truly in danger,’ Ann Jemima declares, fixing her gaze on Mrs Tullett.

‘Indeed he was,’ replies the needlewoman. ‘Imagine what it felt like for him. Sitting in the carriage, surrounded by the angry crowds. Stones smashing against the sides, faces leering and shouting at him. Lord Onslow of the Bedchamber said they thought the stone that came through the window was a bullet at first, it came so fast. It was a miracle it missed the King.’ She purses her lips. ‘He did not act scared at all – but he has said more than once since that he thinks he may well be the last King of England.’

Provis takes a long sip from his cup. ‘We beheaded our King more than a hundred years ago,’ he replies. ‘And what did we get in return for it? Oliver Cromwell, who shut down our inns and theatres, and whipped boys for playing football on a Sunday. In France it has been yet worse. They sent their King to the guillotine but two years ago. It all started with jubilations, but then the radicals brought in the Reign of Terror. Tens of thousands beheaded on the streets in the name of liberty.’ His lip curls. ‘Now France is at war with half of Europe including ourselves. I think it will be a while before the English truly have the appetite to kill another monarch.’

‘Maybe you are right,’ says Mrs Tullett, ‘but I think the King should be worried. People are hungry, Mr Provis. I’ve got cousins who can’t afford bread, and we all know people who are suffering from the bad harvests this year. What more will they endure before he is punished for it?’

The Optickal Illusion

The Optickal Illusion