- Home

- Rachel Halliburton

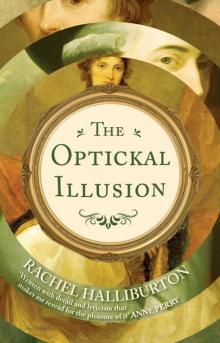

The Optickal Illusion Page 8

The Optickal Illusion Read online

Page 8

He frowns, and starts to write once more.

‘I have had much on my mind reecently, and feel the want of a dear Friend like yourself to talk with. The Atlantick has never felt so wide as it has in reecent weeks, nor indeed has London ever felt so small. I have been here some thirty-three years now, yet on some days I feel more of a Stranger than I did when I first struck these shores.’

For a moment he imagines the world and its oceans spreading around him – the rivers, mountains, great plains and deserts. He thinks of himself as a small dot within that world, and of the political events that are changing it daily. As Britain huddles on the map, to one side the young General Napoleon is leading the French army across Italy and central Europe, surprising the world with victory after victory. To the other side, America has just elected its second president, John Adams. Yet for one of West’s nieces, all these events have been eclipsed by the arrival of an elephant in New York. ‘Such a strange and wond’rous beast you have never seen, dear Uncle,’ she has written. ‘So ugly in each individual detail – the tiny eyes, the discolour’d teeth, the grey pallor of the wrinkly skin, the absurd little tail. Yet in sum so dignified.’

Such is life, West thinks to himself. In so many details, so filled with ugly absurdity. Yet in sum, if not always dignified, certainly a thing to be marvelled at.

‘These days even I find it hard to credit,’ he writes, ‘how bold I was in courting Outrage. I remember that you yourself, with that characteristick Skeptycism that I have come to value so dearly throughout my life, expressed Amazement when I wrote to you that I had enter’d a dispute with both Sir Joshua Reynolds and the King. I was thirty-two, so not a young man – yet still I was fill’d with the spirit of vigorously Questioning all that I set out to do.’

His education in Europe has not improved his ability to spell. He suspects now that it is one of the causes of his stubbornness – the memories of his schoolmaster hitting him on the knuckles and berating his stupidity still linger. Fear of the scorn he will court through his mistakes is a demon he must wrestle every time he writes.

‘That argument prov’d one of my defyning moments,’ he continues. ‘I desired to paint the great Battel of the Plains of Abraham that the British fought in North America in 1759. It was a battel that seem’d to change everything in Britain’s favour.’ A smile flickers on his lips. ‘No one knew then that we were living in a century of political Earthquakes. Certainly no-one in London could imagyne that in fewer than twenty years America would declare independence.’

He shakes his head, lost in thought for a moment.

‘The convention was that historic figures in paintings wore togas. But this made no sense to me. I believed the time was ripe for change. “No”, said I. “They shall wear what they did on the battlefield. When the Romans had their Empyre, they did not even know that North America existed. If Julius Caesar could not have imagined it on a map, why should I paint the men who fought there in togas?” No-one could give me a sensible answer. So I created the first historical painting without Classical attire. From what some persons said, I was about to walk into the jaws of Hell.’

Sir Joshua Reynolds looms before him. He remembers how the great man had summoned him to his house. When West had entered his study, there had been a sense of winter in the air. He had never seen Reynolds so severe. After he had offered his counsel and saw West was still not to be diverted from his course, he had entirely lost his composure. As West had retreated, he had shouted that his reputation as a painter would be destroyed forever by this venture.

Dazed by Reynolds’s anger, West had taken his leave and wandered to Lincoln’s Inn Fields to contemplate his future. As he had sat on a bench, a thin, insidious rain had started to fall, stinging his eyes and quickly starting to run down the back of his neck. A homeless man had approached him – the skin on his face raw, almost as if it had been flayed by hunger and exposure to the cold and damp. West had given him a guinea. As he had watched him disappearing, he had made a bargain with himself that if the experiment did not work, he would sell everything he had in England, and set sail for America within the month.

‘I suspected my subject would otherwise be Pleesing to the King,’ he recalls now. ‘The Death of General Wolfe, after all, shewed a British General dying gloriously after Victory against the French. I constructed my picture so that Wolfe – tho’ in contemperory dress – evoked the dying Christ when held by the Vergin Mary. He was surrounded by the doctor who essayed to save him and other heroic commanders from the Campaign. I made certain that my English friends could not forget, either, the bravery of the Mohawk tribesmen. I painted the indiginous warrior prominently in the foreground to the left. You alone will have noted his resemblance to Running Wolf who took us out fishing those many years past.

‘Some critics were outrageous enough to write that my painting did not shew the truth in any event. They said that since General Wolfe died in the heat of battel, it is impossible that all the Personnages in my painting would have been present. To which I replied that there is a purer truth than that which can be observed through the eye alone. It is the truth one has when one is in possession of all the Facts, a truth that thru echo and implication tells a story in full.’

He remembers the elemental force of London’s outrage, how fighting against the scandal had felt for a short while like being a piece of straw tossed in a hurricane. Everywhere he had turned he had been buffeted by disapproval. He had proclaimed he found the sensation invigorating, even as he had been filled with alarm. But he had never confessed to his brother – or indeed himself – till now, how terrified he had been.

‘Today,’ he continues, ‘that picture is seen as my Greatest triumph. After chiding me for it, the King realised that the many among the publick loved it. In the end he himself ordered a copy. Some would say I chang’d all of history painting through what I did. No artist paints historical figures in togas these days. Even you, who have so often rebuk’d me, were forc’d to conced that because of my daring I changed the course of art.

‘Yet it has been a long while since I achieved a great success. Now, it feels that even when I Adheer to the rules, I am chastised. The King – and maybe this is a symptom of his Madness – has threatened these last two years not to attend the Royal Academy Exhibition. He believes I am secretly Sympathetick to the French Revolution, and reminds me bitterly of past conversations we have had about equality. Yet I am no traitor. I recognise there is a Delikate line I must tread as a guest of the King, and tread it I do.’

He dips his quill in the ink.

‘There is but one happy Aspect of my life right now,’ he continues, ‘though I comprehend not precisely what it portends. A young girl, one Ann Jemima, and her father, Thomas Provis, came to me a year ago offering a Manuscript that appears to shew the technique of painting like Titian. I was highly Sceptical when they first appeared. But I think I am able to create an effect through using it that is simultaneously subtil and vibrant. The girl herself has responded well to some of the insights I myself have given her on Titian. She is but young, just seventeen years of age, yet it is worth remembering that when one of our youngest members, Joseph Turner, entered the Academy he himself was no more than fifteen years. What is in little doubt is that she is socially more agreeable than Mr Turner, who when I was with him last was spitting on the canvas – whether for social or artistic Effect I am at a loss to say.

‘There is only one curious aspect of our encounters. When she is not in my presence – and I have met her five or six times now – I have no precise recollection of what her Face is like. I can tell you that it is a pleasant enough Face, and the eyes have a blue Aspect, but were you to ask me to sketch it, I could not. Maybe this is an Instance of old age advancing on me. It is of little matter, but it is not a Problem that has afflicted me in the past.’

He frowns, and stares out of the window as if hoping, if not to find the answer to the question he has raised, at least to be distracted from somet

hing that is starting to discomfit him. The sky’s blue is lit up by angry streaks of pink, carriages clatter back and forth below.

‘Please let me know,’ he eventually writes, ‘whenever you first have the Opertunity – your opinions on these matters, and anything else that Strikes you to be of importance. I hope you will always know how Important your Opinion is to me, even tho’ I have so often ignored it. Forgive me. The older I get, the more I admire your frankness. I wait to hear from you with impatience, and hope this will find you and your Family in health as through mercy mine are.

Your brother,

Benjamin’

He signs the letter with a frown, and makes to put the crow’s quill back in the small copper oval holder that also contains the inkwell. But he miscalculates the force with which this should be done, and the entire holder tumbles to the floor. For a moment he watches the inky puddle disperse into tiny black rivers across the floorboards. The sky outside grows still darker and the pink streaks disappear, yet it is a while before he can stir himself to remedy the situation.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Dealing with Mr Cosway

‘Although from habit, acquired in our earliest infancy, we suppose Colour to exist in Bodies, nevertheless it is evident, and generally acknowledged, that the word Colour denotes no property of Bodies, but simply a modification of our mind, and only marks the particular sensation, which is the consequence of the shock produced in our sight, by such and such luminous corpuscles.’

constant de massoul,

A Treatise on the Art of Painting and the Composition of Colours, 1797

It takes some time for Provis to suspect the one eventuality that had not occurred to him before he and Ann Jemima approached West. He has anticipated ridicule, humiliation, and even outright denunciation. In rarer moments he has anticipated success. What he has not anticipated is that West might have a hidden agenda. Yet after a few months, this seems the only plausible explanation for what is going on.

Provis’s long experience of doing deals means he has a nose for the right way to set things up before, as he and Darton describe it, going into battle. Normally he himself is well acquainted with the person to whom he is trying to sell – he knows their predilections and perversions, senses as he talks to them what might tilt them one way or another. This has, he believes, put him in exactly the right place for advising Ann Jemima on the best way to try and sell the document. Yet in this situation he has needed to rely not just on Ann Jemima’s perceptions, but on the perceptions of the man who has introduced her to West. Richard Cosway – even the sound of the name makes the bile surge in his throat. ‘But now,’ he whispers to himself, ‘I must treat him as a brother till this whole wretched business is over.’

Cosway, a society portraitist, resembles a diseased fox with his fading red hair and jagged teeth. Rheumy eyes glisten malignantly, while the mouth is rigid with spite and regret. Once the face is animated it becomes more acceptable – an easy, caressing voice lends it a charm that has helped it gain admission to the drawing rooms of Queen Charlotte among others. Yet it is in repose that the face reveals most, and it is in this state that Cosway’s exhausted cynicism is on full display.

Provis still does not know how Cosway discovered what made him walk away from his family in Somerset almost two decades ago. He had decided to amputate his past as if it were a gangrenous limb. Against the roar and chatter of London life, personal details were a luxury in which he could choose not to indulge. He knew some speculated that he had committed some kind of crime – he had overheard the whispers among those who worked with him. Yet in the absence of evidence or any direct accusation, more people indulged him by assuming he was concealing his past because of some personal tragedy. It was known his wife was dead, and that Ann Jemima had been raised by her grandmother. But that was all that was certain. There was something about the man that meant nobody dared to ask him about it outright. Yet Cosway knew. And though he was silent on the matter now, there was an unspoken understanding in all their dealings that if the information ever became valuable enough to him he would have no compunction in sharing it.

Shortly after Ann Jemima had arrived to live with Mr Provis two years beforehand, the portraitist had called at their apartment. From the start there was something precarious about his politeness, as if it were crafted from eggshells. Something is about to break, thought Provis to himself, and I cannot tell what.

‘I have been hearing most favourable reports of Ann Jemima in recent months,’ he began. ‘It seems she has changed quite considerably since you sent her to school in Highgate. She has transformed from a petulant brat into a young lady.’

He did not look directly at Provis, but walked up to the ivory sphinx on the mantelpiece and lifted it to examine it.

‘She is faring better than any of us had dared to hope,’ replied Provis, watching Cosway distrustfully as he made his way over to the window with the sphinx to hold it closer to the light. ‘The palace can be an invidious environment for those who are not used to it. But since she came to live here she has adapted admirably.’

Cosway turned round. ‘Is this Assyrian?’

‘No, it is Ancient Greek. As you will see it is female. The Assyrian variety is normally male.’

‘The detail of the nemes is exquisite.’

He ran a dry finger across the headdress. Provis felt the loathing surge.

‘May I ask what the purpose is of your visit, Mr Cosway?’

Slowly and deliberately Cosway placed the sphinx back on the mantelpiece.

‘I would like to do you a good turn, Mr Provis,’ he said, turning.

What bait do you lay for me? thought Provis.

Out loud he said, ‘I’m sure that is not necessary, Mr Cosway.’

‘You took quite a risk at my behest.’

‘We have often found ourselves in a good position to help each other.’ He tried to mask the resentment in his voice. ‘I did what I thought I should do – no more, no less.’

‘Even so I should like to help you further.’

Cosway came closer – Provis could see the red veins in his eyes.

‘Most young ladies who fare well in polite society possess a skill,’ he declared. ‘They play the piano or learn embroidery. Such attributes can make them highly marriageable, as long as they are not vulgar enough to excel at what they do.’

I must wait, reflected Provis grimly. Soon the mechanism of the trap will be revealed.

He nodded his head, acknowledging the sour wisdom of Cosway’s comment.

‘Does Ann Jemima remain interested in painting?’

‘I would say it is more like an obsession.’

‘I would like to offer her tuition.’

And now he plays his hand, thought Provis.

‘That is most kind of you, but I must refuse your offer,’ he replied shortly. ‘She was taught by a man called Septimus Green when she lived in the country. Now she is happy to instruct herself from books…’

‘Play not the over-protective father,’ interrupted Cosway, coldly amused. ‘Who was this drawing master? Some desiccated old bore who helped her trace the reproductive organs of honeysuckle?’

An unspoken reply curdled in Provis’s stomach.

‘As you know, I have some standing as a teacher,’ Cosway continued. ‘I would not charge you for the first lessons. Though I know you are a proud man, Mr Provis. If you were happy with her progress, and wished to pay for her to continue I would not turn you down. The debt collectors have proved most cantankerous of late.’

There was a fleck of spit on his lip. Sensing it, he moved his hand up uneasily to wipe it away. His learning and sophistication are like gossamer round a rat’s corpse, thought Provis. They cannot disguise the rank odour of self-disgust that lies beneath them.

Cosway’s eyes darkened for a moment as he saw Provis hesitate again. ‘Do not be afraid. You should be well aware you have nothing to concern you regarding my conduct. I know my wife was my painting pu

pil…’

‘Your former wife.’

‘Quite.’

‘I hear,’ Provis cleared his throat, ‘that she has acquired quite a reputation on the Continent.’

If Cosway’s laugh had been cracked open, there would have been dust in it.

‘I have been taunted for the fact I did not want her to be an artist at all. You know as well as I do how the desire to paint seriously can taint a woman’s sexual reputation.’

‘In truth I had not considered that.’

‘Now she is a most successful artist. In France especially she has many admirers. It has been a harsh lesson. I have realised, too late, that my attempts to constrain Maria’s talent bred a resentment from which our marriage never truly recovered.’

Suddenly an expression of such desolation came over his face, that for a moment it felt like an intrusion for Provis even to look at him. It was there just briefly, then he reasserted himself.

‘Do not misread me. I am not in accord with scribblers like Mary Wollstonecraft who say that all women must be educated. On most women – and indeed on certain men – education is as wasted as an opium enema on a dog. Yet Maria has taught me that if a young woman has ability, and a certain determination, then that ability should be cultivated. It is partly my desire to atone for my treatment of my wife that leads me to offer these lessons to Ann Jemima.’

Again it was as if the mask had fallen from his face. Provis looked directly at him this time, trying to read him. Is it possible that his offer is prompted by genuine concerns, he asked himself. Even a man as repugnant as Cosway is occasionally capable of heartfelt sentiment. Yet quickly suspicion reasserted itself in the shadows of his mind. This man has deceived and deceived again, he reminded himself. He looked down at Cosway’s fingers, which twitched uneasily, often a telltale sign of mendacity in his experience. After all, he thought wryly, how often does the deceiver play penitence as his first card?

The Optickal Illusion

The Optickal Illusion